Saturday, December 10, 2022 // Catrin Einhorn and Lauren Leatherby / New York Times

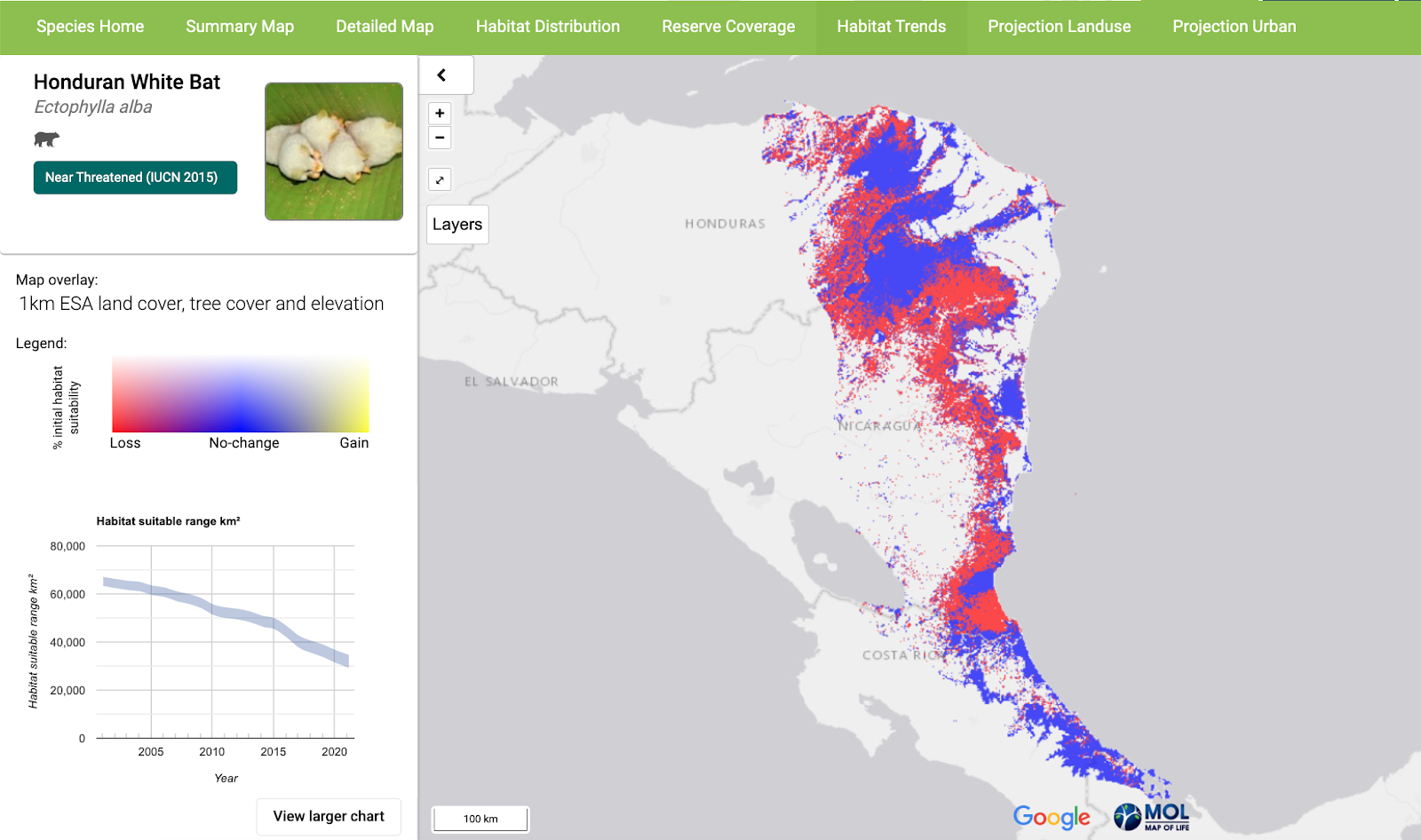

33%, 45%, even upwards of 60% – these are the staggering amounts of suitable habitat some species have lost in the past two decades alone, leaving them struggling to cling on in a dramatically changing world.

This habitat change data, calculated by the Map of Life as part of our Species Habitat Index, was featured prominently in a recent New York Times article “Animals Are Running Out of Places to Live."

“Can we find a way to share the planet with the rest of its inhabitants?” rings the plea from the article, which shares the faces of those species facing the most severe habitat loss – species like the miniscule Honduran White Bat, which has suffered a 53% loss of suitable habitat area and a 46% decrease in habitat connectivity since 2001, and the Madagascar-endemic White-Fronted Brown Lemur, which has lost 40% and 36% of its habitat area and connectivity, respectively.

The Species Habitat Index is one among our suite of biodiversity indicators that measures annual, species-level change in habitat as well as nationally-aggregated indices. Fusing remotely sensed environmental layers with species occurrence, distribution, and trait data, we calculate the change in suitable habitat area and connectivity for tens of thousands of terrestrial vertebrate species over two decades to track how ecosystem integrity and species populations change over time. The Species Habitat Index addresses Goal A of the Convention on Biological Diversity’s Post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework:

Goal A: The integrity of all ecosystems is enhanced, with an increase of at least 15 per cent in the area, connectivity and integrity of natural ecosystems, supporting healthy and resilient populations of all species, the rate of extinctions has been reduced at least tenfold, and the risk of species extinctions across all taxonomic and functional groups, is halved, and genetic diversity of wild and domesticated species is safeguarded, with at least 90 per cent of genetic diversity within all species maintained.

The NYT article highlights the crucial decisions currently underway at the COP15 in Montreal, where BGC Center members are leading conversations about the implementation of the biodiversity indicators for national monitoring and conservation decision making.

Read the full article on the New York Times and learn more about the Species Habitat Index at here.

Thursday, August 12, 2021 // Bill Hathaway / Yale News

As the world’s nations prepare to set new goals for protecting biodiversity, Yale researchers have identified where data gaps continue to limit effective conservation decisions.

In a new study, a team of researchers created maps and assessed regional trends in how well existing species data are able to represent the distribution of 31,000 terrestrial vertebrates worldwide and therefore help inform policies and actions for sustaining biodiversity and its benefits.

“These maps highlight the most rewarding opportunities for citizen scientists, and government agencies, and scientists to support biodiversity monitoring and help close critical knowledge gaps,” said Walter Jetz, professor of ecology and evolutionary biology and of the environment, director of the Yale Center for Biodiversity and Global Change (BGC), and senior author of the paper.

The study was published Aug. 10 in the journal PLOS Biology.

The need for such information is critical as environmental and policy leaders continue to create strategies to protect species diversity worldwide as part of the Convention on Biological Diversity, an international treaty with the aim of conserving and managing global biodiversity which is assessing progress towards those goals.

Jetz and his team have created one of the key tools used by world leaders to monitor, research, and create policies that protect species worldwide — the Map of Life.

In the new study, the researchers present a framework to help pinpoint where additional monitoring is most needed. While there has been a dramatic increase in the amount of data collected on vertebrate species in the past 20 years, they find, not all of this data has yielded new insights on biodiversity. For instance, data on bird species shared by citizen scientists and others tend to be redundant due to the popularity of certain species commonly found in highly populated areas. Most new data collected on birds are from the same species and places.

The analysis was conducted by Yale’s Ruth Oliver, an associate research scientist at the Center for Biodiversity and Global Change, Jetz, and colleagues.

Alarmingly, the study finds that data critical for characterizing biodiversity in many countries has levelled off or, in some cases, even decreased. According to the analysis, 42% of countries have inadequate information on vertebrate biodiversity and have seen either no increase or a decrease in data coverage. Only 17% of countries have achieved sufficient data coverage and also seen an increase in new information on species.

“We hope our work quantifying the tremendous complementary value of observations of underreported biodiversity can support more effective data collection going forward,” Oliver said. “It’s amazing how much we still don’t know about the known species on this planet.”

While the indices used in the study were used to demonstrate the biological diversity of terrestrial vertebrates, they can be readily updated as new data becomes available and expanded to other taxa, such as marine and invertebrate species. This work is supported by the Map of Life team and the results are available for exploration at mol.org/indicators/coverage.

View the article on Yale News

Tuesday, March 23, 2021 // Elizabeth Pennisi / Science

Ecologists involved in mapping all life on Earth have now taken the next step: predicting where the life we don’t know about is waiting to be discovered. As a first pass, they have created an interactive map showing diversity hot spots with the richest potential for new mammal, bird, reptile, and amphibian species. They describe their results today in Nature Ecology & Evolution.

“Unknown species are usually left out of conservation planning, management, and decision-making,” says co-author Mario Moura, an ecologist at the Federal University of Paraíba. “If we want to improve biodiversity conservation worldwide, we need to better know its species.”

It never sat well with Moura that an estimated 85% of Earth’s species are still undescribed. So, in 2018, this newly minted Ph.D. in ecology teamed up with ecologist Walter Jetz at Yale University to come up with a way to better predict where those unknowns are. “The chances of being discovered and described early are not equal among species,” Moura explains. For example, large mammals living near people are much more likely to have been documented by scientists than tiny frogs living in a remote jungle.

View the article on Science

Tuesday, July 23, 2019 // Kasha Patel / Nasa Earth Observatory

In 1983, around 40,000 Nile lechwes (Kobus megaceros) roamed South Sudan and eastern Ethiopia. By 2060, this endangered population of African antelope may be on the brink of extinction. The cause? Loss of wild habitat.

This antelope is just one of hundreds of species that may be imperiled in the next four to five decades, according to a recent NASA-funded study. Researchers from Yale University examined the habitats of 19,400 species to learn how they might be affected by human land-use and encroachment, such as urban development and deforestation. They found that habitats for nearly 1,700 bird, mammal, and amphibian species are expected to shrink about 6 to 10 percent per decade by 2070, greatly increasing the risk of extinction for these animals.

“We all want to see economic progress and development, and that necessarily implies further human-induced changes to landscapes,” said Walter Jetz, co-author of the study and professor of ecology at Yale. “But unless potential impacts of this land use on biodiversity are known and addressed in some form, the long-term consequences could lead to species forever lost for future generations.”

The maps on this page show the potential decrease of suitable habitats for two vulnerable species. The map above shows the habitat change for the Nile lechwes from 2015 (left) to 2070 (right). The antelope species could lose approximately 70 percent of its suitable habitat and become “critically endangered” by 2070.

The map below shows the habitat of Oreophryne monticola, a frog endemic to Indonesia. The frog is currently listed as “endangered” and is predicted to lose more than 50 percent of its habitat in Lombok and Bali by 2070.

“If a country is projected to see a lot of change of swamps or forest to agriculture, this a good predictor that some species in that area are in jeopardy,” said Jetz. “That doesn’t mean these species are necessarily going to go extinct, but they are going to be put under pressure.”

According to the study, amphibians will be the most affected by human land use, followed by birds and mammals. Geographically, species living in South America, Southeast Asia, Central and East Africa, and Mesoamerica are expected to experience the most habitat loss and the greatest increase of extinction risk.

To make these predictions, Jetz and co-author Ryan Powers created a model that allowed them to analyze 2015 habitat conditions of about 19,400 species under anticipated changes in land-use in these areas.

To first estimate the area of suitable habitats in 2015, the team used several remote sensing layers. Elevation data came from Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM) and the Advanced Spaceborne Thermal Emission and Reflection Radiometer (ASTER). Tree cover data came from the Global Forest Change data set, which uses Landsat data to document global tree cover gains and losses.

The researchers then ran a model combining this habitat suitability information with future land-cover projections from the Land Use Harmonization data set in order to estimate decadal changes from 2015 to 2070. They ran the numbers under four different socioeconomic scenarios that would bring variations in land use. (The maps on this page show the “middle-of-the-road” economic scenario and assume no land will be recovered once destroyed.) Even in the best cases, many species are predicted to experience habitat losses by 2070.

“Even though we might see certain losses into the future no matter what we do,” said Jetz, “we can adjust to have the greatest chance of preserving life.” The study could help future conservation efforts by local, national, and international organizations.

The research by Jetz and Powers feeds into an initiative called the Map of Life, a NASA-funded public web platform designed to integrate large amounts of biodiversity and environmental data from researchers and citizen scientists. The global database aims to support a worldwide monitoring of species distributions.

NASA Earth Observatory images by Lauren Dauphin, using data from Powers, Ryan, et al. (2019).

View article on NASA Earth Observatory

Tuesday, March 5, 2019 // Kendall Teare / YaleNews

As humans continue to expand our use of land across the planet, we leave other species little ground to stand on. By 2070, increased human land-use is expected to put 1,700 species of amphibians, birds, and mammals at greater extinction risk by shrinking their natural habitats, according to a study by Yale ecologists published in Nature Climate Change.

To make this prediction, the ecologists combined information on the current geographic distributions of about 19,400 species worldwide with changes to the land cover projected under four different trajectories for the world scientists have agreed on as likely. These potential paths represent reasonable expectations about future developments in global society, demographics, and economics.

“Our findings link these plausible futures with their implications for biodiversity,” said Walter Jetz, co-author and professor of ecology and evolutionary biology and of forestry and environmental studies at Yale. “Our analyses allow us to track how political and economic decisions — through their associated changes to the global land cover — are expected to cause habitat range declines in species worldwide.”

"While biodiversity erosion in far-away parts of the planet may not seem to affect us directly, its consequences for human livelihood can reverberate globally." -Walter Jetz

The study shows that under a middle-of-the-road scenario of moderate changes in human land-use about 1,700 species will likely experience marked increases in their extinction risk over the next 50 years: They will lose roughly 30-50% of their present habitat ranges by 2070. These species of concern include 886 species of amphibians, 436 species of birds, and 376 species of mammals — all of which are predicted to have a high increase in their risk of extinction.

Among them are species whose fates will be particularly dire, such as the Lombok cross frog (Indonesia), the Nile lechwe (South Sudan), the pale-browed treehunter (Brazil) and the curve-billed reedhaunter (Argentina, Brazil, Uruguay) which are all predicted to lose around half of their present day geographic range in the next five decades. These projections and all other analyzed species can be examined at the Map of Life website.

“The integration of our analyses with the Map of Life can support anyone keen to assess how species may suffer under specific future land-use scenarios and help prevent or mitigate these effects,” said Ryan P. Powers, co-author and former postdoctoral fellow in the Jetz Lab at Yale.

Species living in Central and East Africa, Mesoamerica, South America, and Southeast Asia will suffer the greatest habitat loss and increased extinction risk. But Jetz cautioned the global public against assuming that the losses are only the problem of the countries within whose borders they occur.

“Losses in species populations can irreversibly hamper the functioning of ecosystems and human quality of life,” said Jetz. “While biodiversity erosion in far-away parts of the planet may not seem to affect us directly, its consequences for human livelihood can reverberate globally. It is also often the far-away demand that drives these losses — think tropical hardwoods, palm oil, or soybeans — thus making us all co-responsible.”

The study was funded by grants from the National Science Foundation, the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

View article on Yale News

Wednesday, August 15, 2018 // Kendall Teare / YaleNews

The International Cooperation for Animal Research Using Space, or ICARUS, will be flying closer to the sun than ever when a pair of Russian cosmonauts installs the antennae for its state-of-the-art animal tracking system on the exterior of the International Space Station on Aug. 15. The installation will be one small step for the cosmonauts and one giant leap for Yale biodiversity research.

Thanks to the recently founded Max Planck-Yale Center (MPYC) for Biodiversity Movement and Global Change, Yale and U.S.-based biodiversity researchers will be among the first to make use of the big data that this groundbreaking scientific instrument will be collecting by early 2019.

For the past 16 years, ICARUS has been simultaneously developing the tiniest transmitters (by 2025, the team hopes to scale down solar-powered backpacks enough to fit them on desert locusts) and some of the most massive antennae (the equipment that the cosmonauts will be installing). Together, these two new technologies will give biodiversity researchers an unprecedented, extraterrestrial perspective on the lives of some of Earth’s smallest and most mobile creatures, such as fruit bats, baby turtles, parrots, and songbirds.

“The system represents a quantum leap for the study of animal movements and migration, and will enable real-time biodiversity monitoring at a global scale,” said Walter Jetz, professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at Yale and co-director of the MPYC.

"I expect ICARUS to exceed what has existed to date by at least an order of magnitude and someday potentially several orders." -walter jetz

“In the past, tracking studies have been limited to, at best, a few dozen simultaneously followed individuals, and the tags were large and readouts costly,” added Jetz. “In terms of scale and cost, I expect ICARUS to exceed what has existed to date by at least an order of magnitude and someday potentially several orders. This new tracking system has the potential to transform multiple fields of study.”

Even with the limited tracking technology available, biodiversity researchers have already been able to predict volcanic eruptions by tracking the movements of goat herds and understand impacts of climate change by following migration changes in birds. This new space station-based system will allow researchers to see “not only where an animal is but also what it is doing,” explained Martin Wikelski, chief strategist for ICARUS, director of the Max Planck Center for Ornithology, and co-director with Jetz of the MPYC.

“At a global scale, we will be able to monitor individual animal behaviors as well as get a grasp of their intricate life histories and interactions with each other,” said Wikelski. In addition to positional coordinates, the transmitters are able to capture each animal’s acceleration, alignment to the magnetic field of Earth, and moment-to-moment environmental conditions, including ambient temperature, air pressure, and humidity.

The technology provides an exciting tool to monitor changing wildlife and the connectivity of landscapes for conservation and public health, explained Jetz. Researchers will be able to apply this new language of mass animal movement to everything from greater forewarning of geological disasters, such as earthquakes and volcanic eruptions, to monitoring the next potential disease outbreak in humans. For example, Wikelski plans to use the new system to advance his own project of tracking the movement of African fruit bats as sentinels for finding the hosts of the Ebola virus. (Fruit bats have antibodies against, but do not transmit, this deadly disease.)

“Tracked animals can act as intelligent sensors and biological sentinels and in near real-time inform us about the biodiversity effects of ongoing environmental change,” explained Jetz.

By the beginning of 2019, Wikelski and colleagues will have 1,000 transmitters in the field, but eventually, they hope to grow that number to 100,000. Every time a transmitter enters the International Space Station’s beam — roughly four times daily — it may send up a data packet of 223 bytes. From there, the data will be relayed back to the ground station and subsequently distributed to research teams. All data — except sensitive conservation data such as rhino locations — will also be published on the publicly accessible database MoveBank, and will inform maps and trends in Map of Life, a web-based initiative headed by Jetz that integrates global biodiversity evidence.

As with all fields of scientific research, however, the data are only as good as their processing and analysis. MPYC will be the primary initial interpreter of the big data harvested by the ICARUS satellite. Fortunately, Jetz notes, with Yale’s investment in integrative data science as a research priority, MPYC can handle the big data sets that the ICARUS tracking system generates.

“Going back to my own Ph.D. work observing and tracking nocturnal birds in Africa with much inferior technology,” said Jetz, “I was always driven by the wish to document and understand biodiversity from the level of the individual up to the global scale.”

“The new technology will allow us to put the bigger picture together,” Jetz continued. “Thanks to the near-global scale of ICARUS and satellite-based remote sensing of the environment, we are finally able to connect individual behaviors and decisions with the use of space and environments at large scales. Our collaboration with Max Planck and ICARUS is a wonderful enabler of and complement to our work at Yale.”

View article on Yale News

Tuesday, July 31, 2018 // Medium

The Significance of Biodiversity

Biodiversity is the variety of life on Earth, the building blocks of functioning ecosystems that provide the natural services on which all life depends, including people. Species, the fundamental units of biodiversity, are in the midst of an extinction crisis, losing ground globally at a rate 1,000 times greater than at any time in human history due to factors like habitat loss and climate change.

How do we stop this? Knowing where species live and the pressures threatening them is paramount in reversing the extinction crisis and maintaining the health of our planet, for ourselves and for future generations. As the impact of humans increasingly encroaches on critical habitats everywhere, determining ‘where’ to protect is just as critical as ‘how much’ to protect.

Tuesday, March 6, 2018 // Half-Earth Project

THE HALF-EARTH PROJECT IS ‘UNLOCKING A NEW ERA IN DATA-DRIVEN CONSERVATION.’

The Half-Earth Project has launched online the first phase of their cutting-edge global biodiversity map. This unique, interactive asset uses the latest science and technology to map thousands of species around the world and illuminate where future conservation efforts should be located to best care for our planet and ourselves.

“The extinction of species by human activity continues to accelerate, fast enough to eliminate more than half of all species by the end of this century,” said E.O. Wilson in the New York Times Sunday Review on March 3. “We have to enlarge the area of Earth devoted to the natural world enough to save the variety of life within it. The formula widely agreed upon by conservation scientists is to keep half the land and half the sea of the planet as wild and protected from human intervention or activity as possible.”

Born from Wilson’s book Half-Earth: Our Planet’s Fight for Life, the Half-Earth Project is providing the urgently needed research, leadership and knowledge necessary to conserve half the planet’s surface. The new map sits at the center of this effort. By mapping the biodiversity of our planet, we can identify the best places to conserve to safeguard the maximum number of species.

“The Half-Earth Project is mapping the fine distribution of species across the globe to identify the places where we canprotect the highest number of species,” Wilson said. “By determining which blocks of land and sea we can string together for maximum effect, we have the opportunity to support the most biodiverse places in the world as well as the people who call these paradises home.”

The Half-Earth Project is targeting completion of the fine-scale species distribution map for most known terrestrial, marine, and freshwater plant and animal species within 5 years.

“This mapping tool is unlocking a new era in data-driven conservation,” said Paula Ehrlich, President and CEO of the E.O. Wilson Biodiversity Foundation and head of the Half-Earth Project. “It will provide the scientific foundation upon which communities, scientists, conservationists and decision-makers can achieve the goal of Half-Earth.”

A $5 million leadership gift from E.O. Wilson Biodiversity Foundation board member Jeff Ubben and his wife Laurie will seed the second phase of the Half-Earth Project’s mapping effort.

“Half-Earth can’t wait. We have to work quickly and we need to be smart about how we do the work,” said Jeff Ubben. “This map will give us the information we need to make strong conservation investments.”

“Ed Wilson framed Half-Earth as a moonshot necessary to preserve the future health of our planet,” Ehrlich said. “The investment in our work from Jeff and Laurie Ubben attaches rocket boosters to this moonshot.”

View article on Half-Earth Project

Monday, March 5, 2018 // New York Times

The history of conservation is a story of many victories in a losing war. Having served on the boards of global conservation organizations for more than 30 years, I know very well the sweat, tears and even blood shed by those who dedicate their lives to saving species. Their efforts have led to major achievements, but they have been only partly successful.

The extinction of species by human activity continues to accelerate, fast enough to eliminate more than half of all species by the end of this century. Unless humanity is suicidal (which, granted, is a possibility), we will solve the problem of climate change. Yes, the problem is enormous, but we have both the knowledge and the resources to do this and require only the will.

The worldwide extinction of species and natural ecosystems, however, is not reversible. Once species are gone, they’re gone forever. Even if the climate is stabilized, the extinction of species will remove Earth’s foundational, billion-year-old environmental support system. A growing number of researchers, myself included, believe that the only way to reverse the extinction crisis is through a conservation moonshot: We have to enlarge the area of Earth devoted to the natural world enough to save the variety of life within it.

The formula widely agreed upon by conservation scientists is to keep half the land and half the sea of the planet as wild and protected from human intervention or activity as possible. This conservation goal did not come out of the blue. Its conception, called the Half-Earth Project, is an initiative led by a group of biodiversity and conservation experts (I serve as one of the project’s lead scientists). It builds on the theory of island biogeography, which I developed with the mathematician Robert MacArthur in the 1960s.

Island biogeography takes into account the size of an island and its distance from the nearest island or mainland ecosystem to predict the number of species living there; the more isolated an ecosystem, the fewer species it supports. After much experimentation and a growing understanding of how this theory works, it is being applied to the planning of conservation areas.

So how do we know which places require protection under the definition of Half-Earth? In general, three overlapping criteria have been suggested by scientists. They are, first, areas judged best in number and rareness of species by experienced field biologists; second, “hot spots,” localities known to support a large number of species of a specific favored group such as birds and trees; and third, broad-brush areas delineated by geography and vegetation, called ecoregions.

All three approaches are valuable, but applying them in too much haste can lead to fatal error. They need an important underlying component to work — a more thorough record of all of Earth’s existing species. Making decisions about land protection without this fundamental knowledge would lead to irreversible mistakes.

The most striking fact about the living environment may be how little we know about it. Even the number of living species can be only roughly calculated. A widely accepted estimate by scientists puts the number at about 10 million. In contrast, those formally described, classified and given two-part Latinized names (Homo sapiens for humans, for example) number slightly more than two million. With only about 20 percent of its species known and 80 percent undiscovered, it is fair to call Earth a little-known planet.

Paleontologists estimate that before the global spread of humankind the average rate of species extinction was one species per million in each one- to 10-million-year interval. Human activity has driven up the average global rate of extinction to 100 to 1,000 times that baseline rate. What ensues is a tragedy upon a tragedy: Most species still alive will disappear without ever having been recorded. To minimize this catastrophe, we must focus on which areas on land and in the sea collectively harbor the most species.

Building on new technologies, and on the insight and expertise of organizations and individuals who have dedicated their lives the environment, the Half-Earth Project is mapping the fine distribution of species across the globe to identify the places where we can protect the highest number of species. By determining which blocks of land and sea we can string together for maximum effect, we have the opportunity to support the most biodiverse places in the world as well as the people who call these paradises home. With the biodiversity of our planet mapped carefully and soon, the bulk of Earth’s species, including humans, can be saved.

By necessity, global conservation areas will be chosen for what species they contain, but in a way that will be supported, and not just tolerated, by the people living within and around them. Property rights should not be abrogated. The cultures and economies of indigenous peoples, who are de facto the original conservationists, should be protected and supported. Community-based conservation areas and management systems such as the National Natural Landmarks Program, administered by the National Park Service, could serve as a model.

To effectively manage protected habitats, we must also learn more about all the species of our planet and their interactions within ecosystems. By accelerating the effort to discover, describe and conduct natural history studies for every one of the eight million species estimated to exist but still unknown to science, we can continue to add to and refine the Half-Earth Project map, providing effective guidance for conservation to achieve our goal.

The best-explored groups of organisms are the vertebrates (mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, fishes), along with plants, especially trees and shrubs. Being conspicuous, they are what we familiarly call “wildlife.” A great majority of other species, however, are by far also the most abundant. I like to call them “the little things that run the world.” They teem everywhere, in great number and variety in and on all plants, throughout the soil at our feet and in the air around us. They are the protists, fungi, insects, crustaceans, spiders, pauropods, centipedes, mites, nematodes and legions of others whose scientific names are seldom heard by the bulk of humanity. In the sea and along its shores swarm organisms of the other living world — marine diatoms, crustaceans, ascidians, sea hares, priapulids, coral, loriciferans and on through the still mostly unfilled encyclopedia of life.

Do not call these organisms “bugs” or “critters.” They too are wildlife. Let us learn their correct names and care about their safety. Their existence makes possible our own. We are wholly dependent on them.

With new information technology and rapid genome mapping now available to us, the discovery of Earth’s species can now be sped up exponentially. We can use satellite imagery, species distribution analysis and other novel tools to create a new understanding of what we must do to care for our planet. But there is another crucial aspect to this effort: It must be supported by more “boots on the ground,” a renaissance of species discovery and taxonomy led by field biologists.

Within one to three decades, candidate conservation areas can be selected with confidence by construction of biodiversity inventories that list all of the species within a given area. The expansion of this scientific activity will enable global conservation while adding immense amounts of knowledge in biology not achievable by any other means. By understanding our planet, we have the opportunity to save it.

As we focus on climate change, we must also act decisively to protect the living world while we still have time. It would be humanity’s ultimate achievement.

View article on the New York Times

Thursday, December 21, 2017 // Google Cloud Platform

About Map of Life

Map of Life supports global biodiversity education, monitoring, research, and decision-making by integrating and analyzing global information about species distributions and dynamics. Using hosted cloud technology, Map of Life makes its data available to scholars, researchers, students, teachers, and conservationists.

Industries: Education, Non-profit

Location: United States

Products: App Engine, BigQuery, Cloud SQL, Cloud Storage, Compute Engine, Google Earth Engine

Map of Life supports biodiversity education, monitoring, research, and decision-making by using Google Cloud Platform products to collect, analyze, and visually represent global data

Stores over 600M records for 44K+ species

Google Cloud Platform Results

Speeds up data analysis required for accurate assessments of endangered species

Provides scientific evidence to support conservation efforts

Scales on demand to support additions and updates to large data volumes

Stores over 600M records for 44K+ species

The richness and diversity of life on Earth is fundamental to the complex systems that inhabit it. But phenomena including climate change, pollution, unsustainable agriculture, and habitat destruction and degradation threaten the planet’s ecosystems and inhabitants. The World Wildlife Fund (WWF) estimates that wildlife populations worldwide declined by 58% between 1970 and 2012.

To reverse such trends, scientists, conservationists, and governments need to know where and how to target efforts to help prevent extinction and preserve biodiversity. Yale University and the University of Florida (UF) partnered to tackle the challenge by collecting and analyzing global sources of data and making information available to help guide research, policy, and conservation.

“Google Cloud Platform offers all the tools we need for large-scale data management and analysis. Its integration with Google Earth Engine makes it ideal for data visualization.”

—Walter Jetz, Associate Professor, Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, Yale University

Their solution, Map of Life, contains data about vertebrates, plants, and insects from international, national, and local sources, including BirdLife International, International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF). Yale and UF chose Google Cloud Platform to support Map of Life’s data storage, analysis, and mapping because of its superior ability to scale, integrate, manage, mine, and display data.

“Google Cloud Platform offers all the tools we need for large-scale data management and analysis,” says Walter Jetz, Associate Professor, Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at Yale University. “Its integration with Google Earth Engine and Google Maps make it ideal for data visualization.”

Mapping where species are at-risk

Map of Life currently draws from more than 600 million records worldwide that contain information about approximately 44,351 species of vertebrates, plants, and insects and more than 700,000 species names, stores the information in Google Cloud Storage. Its scalable, high-performance architecture also includes the Google App Engine platform-as-a-service (PaaS) to host application logic and feed information to various user interfaces via RESTful application program interfaces (APIs). Geolocation and spatial data can be analyzed and displayed through Google App Engine APIs that connect to the Google Earth Engine, and CARTO geolocation data cloud platforms. The Map of Life CARTO service runs on Google Compute Engine virtual machines to improve scalability of on-demand vector mapping and query needs.

Combining data from multiple sources allows Map of Life to estimate the distribution of and trends within at-risk species and make this information available to naturalists, conservation groups, natural resource managers, scientists, and interested amateurs. Anyone who visits the website or downloads the mobile app can view the information.

Google Compute Engine performs complex data analyses to predict which species are at risk. The science behind understanding biodiversity and identifying and predicting trends within species requires multiple analytic iterations, each of which accounts for corrections and new input from scientists. Google Compute Engine is particularly well suited for this because of how quickly it processes each iteration.

“Map of Life uses Google BigQuery to analyze massive data sets, quickly. We can perform a query on 600 million species occurrence records in less than a minute, helping scientists reach conclusions more quickly.”

—Jeremy Malczyk, Lead Software Engineer, Map of Life

“Every day we’re gathering more data, including from remote sensors,” says Walter. “Using Google Cloud Platform and Google Earth Engine, we’re able to make more accurate predictions about at-risk species worldwide.”

Map of Life continually incorporates new data sets, including those from individual observers who submit observations about vertebrates, plants, and insects. The platform even integrates remote-sensing data from Google Earth Engine and uses Google BigQuery to analyze large sets of unstructured data.

“Map of Life uses Google BigQuery to analyze massive data sets, quickly,” says Jeremy Malczyk, Lead Software Engineer for Map of Life. “We can perform a query on 600 million species occurrence records in less than a minute, helping scientists reach conclusions more quickly.”

Global conservation powered by data

More than 100,000 scientists and concerned citizens already use Map of Life for biodiversity research and discovery. Map of Life is also developing new tools and visualizations to support the specific needs of government agencies and conservation organizations to help support the development of environmental policy.

The Chicago Field Museum and Map of Life received a $300,000 MacArthur Foundation grant to support conservation efforts in South America. Map of Life is creating data visualization dashboards for park managers, who can use the biodiversity information to improve conservation strategies in protected areas across Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru.

“Humankind has historically had very little information about biodiversity with sufficient spatial detail at a global scale. Map of Life is setting out to change that,” adds Walter. “By combining in data and models we aim to help everyone from eco-tourists who can appreciate biodiversity wherever they travel, to resource managers who need to handle development in a sustainable way, and to governments who want to protect biodiversity.”

View article on Google Cloud Platform

Friday, June 2, 2017 // JetzLab

Map of Life has released a first suite of maps that aggregate biodiversity patterns. These pages feature global biodiversity patterns based on publications in Nature and PNAS. The types of maps available are:

| Species |

Phylogenetic |

Functional |

| Species Richness |

Phylogenetic Diversity |

Functional Diversity |

| Species Endemism |

Phylogenetic Endemism |

Functional Endemism |

| Local Species Diversity Priority |

Local Phylogenetic Diversity Priority |

Local Functional Diversity Priority |

| Global Species Diversity Priority |

Global Phylogenetic Diversity Priority |

Global Functional Diversity Priority |

Explore these new resources here.

View article on JetzLab

Friday, May 26, 2017 // Yale News

Research by Yale and the University of Grenoble documents where additional conservation efforts globally could most effectively support the safeguarding of species (some examples shown here) that are particularly distinct in their functions or their position in the family tree of life. (Image credits: family tree illustration, Laura Pollock; Solenodon paradoxus photo, Nate Upham; additional photos, Wikipedia.)

A new study finds that major gains in global biodiversity can be achieved if an additional 5% of land is set aside to protect key species.

Scientists from Yale University and the University of Grenoble said such an effort could triple the protected range of those species and safeguard their functional diversity. The findings underscore the need to look beyond species numbers when developing conservation strategies, the researchers said.

“Biodiversity conservation has mostly focused on species, but some species may offer much more critical or unique functions or evolutionary heritage than others — something current conservation planning does not readily address,” said Walter Jetz, a Yale associate professor of ecology and evolutionary biology, and director of the Yale Center for Biodiversity and Global Change.

“We show that a direct consideration of these other biodiversity facets identifies different regions as high-priority for conservation than a focus on species does, and more effectively safeguards functions or evolutionary heritage,” Jetz said. “We find that through the smart placement of conservation areas, strong gains in the conservation of the multiple facets of biodiversity facets are possible.”

The study appears online May 24 in the journal Nature. Laura Pollock of the University of Grenoble is the study’s first author, Jetz is senior author, and Wilfried Thuiller of the University of Grenoble is co-author.

The researchers noted that 26% of the world’s bird and mammal species are not reliably included in protected areas. The outlook for filling gaps in bird and mammal diversity could improve dramatically by smartly expanding the areas currently managed for conservation, they said.

The researchers advocate a conservation strategy that emphasizes global representation, i.e., the planetary safeguarding of species function or evolutionary heritage planet-wide, rather than local representation. They estimate that a carefully prepared 5% increase in conservation area would allow a dramatically improved capture of bird and mammal biodiversity facets; an approach focused on species numbers alone would be much less optimal, the researchers said.

Jetz and his colleagues also said their approach enables a more comprehensive guidance and capture of progress as mandated by the Convention on Biological Diversity and under evaluation by the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services.

“Given the current biodiversity crisis, these results are encouraging because they show big conservation gains are possible for aspects of biodiversity that might otherwise be overlooked in conservation plans,” Pollock said. “This biodiversity is key to retaining the tree of life or functioning ecosystems, which nicely fits declared international policy goals. This approach can be updated and refined as the world’s biodiversity becomes better understood, catalogued, and documented.”

The researchers have created interactive web maps in the Map of Life project to accompany the study. They can be found at: https://mol.org/patterns/facets

The National Science Foundation, the Yale Center for Biodiversity and Global Change, the People’s Programme of the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme, and the European Research Council supported the research.

View article on YaleNews

Wednesday, December 14, 2016 // Google Cloud Platform

Global biodiversity is declining at an unprecedented rate: The World Wildlife Foundation estimates the decline of two thirds of the earth's vertebrate populations by 2020, providing supporting evidence that we are currently in an extinction crisis. With so many species at risk, it’s difficult for scientists, conservationists and government agencies to know how and where to prioritize and target efforts to halt extinctions and preserve biodiversity.

Map of Life, a collaborative project hosted by Yale University and the University of Florida, endeavors to tackle this challenge by providing comprehensive biodiversity information that integrates data from a large number of sources, including museums, conservation groups, government agencies and individuals. It layers an astounding amount of information for hundreds of thousands of species and using a rapidly growing amount of data, currently over 600 million records, on web and mobile-based Google Maps.

Map of Life needed a cloud-based platform to host their considerably large database, and chose Google Cloud Platform because it offers the best scalable tools to integrate, manage, mine and display data, additionally integrating products with Google Earth Engine and Google Maps.

“Google Cloud Platform offers all the tools we needed for large-scale data management and analysis. Its integration with Google Earth Engine and Google Maps make it ideal for data visualization.”

— Walter Jetz, Associate Professor, Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, Yale University.

Pinpointing at-risk species

Combining data from multiple sources, Map of Life provides estimates of the distribution and potential trends of at-risk species and makes this information available to naturalists, conservation groups, resource managers, and global threat assessors. Anyone who visits the website or downloads the app can get information about which species occur where, globally. Google Cloud Storage hosts the data and scales automatically as the amount of information grows. Google App Engine runs a middleware API that integrates the data, makes it available to researchers, and displays it on Google Maps. Google Compute Engine performs data analyses to predict which species are at risk.

In biodiversity science, making predictions is extremely complex and requires many iterations, each of which includes corrections and new input from scientists. Compute Engine is particularly well-suited for this because of how quickly it performs each iteration. That allows more iterations to be run in a given time period.

“Every day we’re gathering more data, including from remote sensors. Using Google Cloud Platform and Google Earth Engine, we’re able to make more accurate predictions about at-risk species worldwide,” says Jetz.

Map of Life continually incorporates new data sets from resources around the world. It also allows people to send in their own observations about birds, mammals, cacti, and many more organisms. This platform integrates remote-sensing data from Google Earth Engine additionally utilizing Google BigQuery to perform queries on very large data sets.

“Map of Life uses Google BigQuery to analyse massive data sets, quickly. We can perform a query on 600 million species occurrence records in less than a minute, helping scientists reach conclusions more quickly,” says Jeremy Malczyk, lead software engineer for Map of Life.

Addressing biodiversity and conservation across the globe

Well over 100,000 scientists and citizen scientists are using Map of Life for biodiversity research and discovery. Map of Life is now developing visualizations and tools to support the specific needs of government agencies and conservation bodies and to help decision-making for environmental policy. In September 2016, the Chicago Field Museum and Map of Life received a $300,000 MacArthur Foundation grant to support conservation efforts in South America. Dashboards will provide park managers with biodiversity information including lists of species expected in a particular location. That information will be used to improve conservation strategies in protected areas within South America.

“Humankind has historically had very little information about biodiversity with sufficient spatial detail at a global scale. With Map of Life are setting out to change that. By combining in data and models we aim to help everyone from ecotourists who can appreciate biodiversity wherever they travel, to resource managers who need to handle development in a sustainable way, and to governments who want to protect biodiversity,” Jetz says.

View article on Google Cloud Platform

Monday, December 12, 2016 // Global Mountain Biodiversity Assessment

The Global Mountain Biodiversity Assessment (GMBA) teamed up with Map of Life (MOL) to launch a new web-portal for the

visualization and exploration of biodiversity data for over 1000 mountain ranges defined worldwide.

Mountains are hotspots of biodiversity and areas of high endemism that support one third of terrestrial species and

numerous ecosystem services. Mountain ecosystems are therefore of prime importance not only for biodiversity, but for

human well-being in general. Because of their geodiversity, mountain ecosystems have served as refuge for organisms

during past climatic changes and are predicted to fulfill this role also under forthcoming changes. Yet, mountains are

responding to increasing land use pressure and changes in climatic conditions, and collecting, consolidating, and

standardizing biodiversity data in mountain regions is therefore important for improving our current understanding of

biodiversity patterns and predicting future trends.

In order to accurately predict potential changes in mountain biodiversity in response to drivers of global changes and

develop sustainable management and conservation strategies, we must be able to define what exactly a mountain is,

where mountains are in the world, and what species currently occur in those mountains.

More than 1000 mountain ranges around the world have now been described in a new study published in Alpine Botany by

Christian Körner et al. (2016). Additionally, and for the first time, this global mountain inventory coverage has

also been combined with expert range maps for approximately 60,000 species across different organismic groups and is

being made available online through the Mountain Portal. The Mountain Portal is an interactive web platform provided

by the Global Mountain Biodiversity Assessment of Future Earth and developed by Map of Life. With just a few clicks

users can explore and download growing lists of mountain ranges and expected species. Downloaded data can then be used

for a multitude of projects ranging from mechanistic studies on the evolution and ecological drivers of mountain

biodiversity to the development of indicators in sustainability research.

The mountain portal is an open source tool for all types of users, ranging from laymen and citizen scientists to

researchers, practitioners, stakeholders and policy makers. It is an evolving resource that will utilize the power of

the global community to improve mountain biodiversity and inventory information.

View article on Global Mountain Biodiversity Assessment

Friday, September 16, 2016 // Yale News

The Yale-led Map of Life project and The Field Museum in Chicago have won a $300,000 MacArthur Foundation grant to support conservation decisions in South America.

The two institutions will work with park services and wildlife agencies in Peru, Ecuador, and Colombia to improve conservation actions by harnessing better information about biodiversity. They will develop online dashboards to provide park managers with demand-driven, actionable biodiversity information such as lists of species expected in a particular location and estimates of their distribution trends. Park staff and visitors will use the service, which will be tailored to each park reserve area.

Map of Life is an online platform for species distributions, led by Walter Jetz, associate professor of ecology and evolutionary biology, and director of the Yale Center for Biodiversity and Global Change. “The new tools will provide biodiversity information specific to single parks and offer reserve managers basic analysis and reporting tools on data gaps and actual conservation gaps in their reserve system,” Jetz said.

Map of Life’s partner in the project, The Field Museum, has helped protect 23 million acres of wilderness in the tropical Andes through its Keller Science Action Center.

For more information, visit:

Map of Life

Keller Science Action Center

MacArthur Foundation

Jetz Lab

View article on Yale News

Tuesday, June 28, 2016 // Yale News

The American Association of School Librarians has named Map of Life, a Yale-led project with the University of Florida that assembles and integrates multiple sources of data about species distributions worldwide, as a 2016 Best App for Teaching & Learning.

The recognition honors apps of “exceptional value to inquiry-based teaching and learning” by fostering innovation, creativity, active participation, and collaboration. The award was announced June 25 at the American Library Association annual conference in Orlando, Florida.

Walter Jetz, associate professor of ecology and evolutionary biology, and director of the Yale Program in Spatial Biodiversity, is the guiding force behind Map of Life.

The Map of Life app puts a wealth of the world’s knowledge about biodiversity in the palm of a user’s hand. It can tell users which species are likely to be found in the vicinity, with photos and text to help identify and learn about species. The app also helps users create personal lists of observations and contribute those lists to scientific research and conservation efforts.

View journal article on Yale News

Tuesday, June 21, 2016 // Map of Life

Despite the central role of species distributions in ecology and conservation, occurrence information remains geographically and taxonomically incomplete and biased. Efforts to address this problem, such as targeted data mobilization and advanced distribution modelling, all crucially rely on a solid understanding of the patterns and determinants of occurrence information. Numerous socio-economic and ecological drivers of uneven record collection and mobilization among species have been suggested, but the generality of their effects remains untested. Here, we provide the first global analysis of patterns and drivers of species-level variation in different metrics of occurrence information.

View journal article on Wiley Online Library

Thursday, April 14, 2016 // Map of Life

Tuesday, April 5, 2016 // New York Times

After countless years of daydreamers being told otherwise, there’s now a good reason to keep your head in the clouds.

Scientists combed through satellite photographs of cloud cover taken twice a day for 15 years from nearly every square

kilometer of Earth to study the planet’s varied environments.

By creating cloud atlases, the researchers were able to better predict the location of plants and animals on land with

unprecedented spatial resolution, allowing them to study certain species, including those that are often in remote places.

The results were published last week in PLOS Biology.

Clouds directly affect local climates, causing differences in soil moisture and available sunlight that drive

photosynthesis and ecosystem productivity.

The researchers demonstrated the potential for modeling species distribution by studying the Montane woodcreeper, a

South American bird, and the King Protea, a South African shrub.

“In thinking about conserving biodiversity, one of the most important scientific questions is ‘Where are the species?’”

said Adam Wilson, an ecologist now

at the University at Buffalo, who led the study. The maps also could help monitor ecosystem changes.

For cloud-gazing, you can download the data: earthenv.org/cloud.html

View article on New York Times

Friday, March 11, 2016 // Deutschlandradio Kultur

Ein digitales Bestimmungsbuch, das über Tiere und Pflanzen Auskunft gibt - wo auch immer man sich aufhält: Die App

"Map of Life" zeigt an, was rund um den eigenen Standort kreucht und fleucht. Die Nutzer können sogar die

Wissenschaft voran bringen.

View article on Deutschlandradio Kultur

Thursday, January 14, 2016 // Green apps & web

Map of Life builds on a global scientific effort to help you discover, identify and record species worldwide.

Map of Life is an application about biodiversity that gathers data from observations and references from numerous databases throughout the world, with information on different animal groups and plants. Some differences were detected between the mobile and the web app version, so they will be described separately.

The mobile app offers a lateral menu with different options:

What’s around me, option based on the geolocation of the user, delimiting an area (the radius is unknown) on which the information is extracted.

Search the map by entering a place name or clicking on the map.

Search for species by common or scientific name.

My records, where you can upload your sightings after opening a free account.

Settings, section where you can select the language or access to the help (only in English), for example.

The information for each species includes a data sheet with a description taken from Wikipedia (in the selected language for the app), a map of geographical distribution and multiple images, in addition to the classification of the IUCN Red List.

The web app is more complete than the mobile version, since from the “Detailed Map” option you can filter information such as the range of years or the uncertainty, related in this case with geolocation errors (less accurate in old sightings and more detailed in actual observations made with modern devices).

View article on Green apps & web

Sunday, October 25, 2015 // GEO BON

Last week, an ad-hoc technical expert group of the CBD met in Geneve to advise CBD on a small set of indicators that could be used to assess progress towards the Aichi targets. GEO BON presented a new generation of indicators based on integrating information from a small set of essential biodiversity variables (http://www.geobon.org/Downloads/brochures/2015/GBCI_Version1.1_low.pdf).

The indicators, developed in collaboration with GEO BON partners Map of Life and CSIRO, were the Species Habitat Indices (Target 5 and 12), the Biodiversity Habitat Index (Target 5), the Species Protection Index Target 11), the Protected Area Representativeness and Connectedness Indices (Target 11), the Global Ecosytem Restoration Index (Target 15), and the Species Status Information Index (Target 19). They are based on global datasets for 4 EBVs: Species Distributions, Taxonomic Diversity (gamma diversity), Ecosystem Extent, and Primary Productivity. The indicators were very well received at the AHTEG, and were adopted as specific examples of indicators for these targets. They also illustrate the power of EBVs as a modelled layer between direct observations and indicators and its potential to generate global indicators and spatial explicit datasets.

View article on GEO BON

Wednesday, September 9, 2015 // Jim Shelton / Yale News

Wealthy, emerging countries that are home to some of the most threatened animals on Earth are also the very places where biological records about animals are most sparse.

A comprehensive survey of global species distribution data, conducted in conjunction with the Yale-based Map of Life team, found that few records are accessible for Brazil, China, India, and several other large, emerging economies.

The survey results appear in the journal Nature Communications. The scientists investigated millions of records about the distribution of all known species of mammals, birds, and amphibians. Most of the records came from natural history museums or regional field surveys that make such information available.

“In our study we show that in most parts of the world, and even in many well-off countries, way too little data has been collected or shared to guide conservation and sustainable resource use,” said co-author Walter Jetz, a Yale University associate professor of ecology and evolutionary biology, and director of the Yale Program in Spatial Biodiversity Science & Conservation.

Jetz is the guiding force behind Map of Life, a project that assembles and integrates multiple sources of data about species distributions worldwide, including a mobile app. “More international data sharing is critical, and efforts such as Map of Life can help guide the efficient collection and use of new information,” Jetz said.

The new study sheds light on exactly where species information is most needed. “Until now it was thought that the largest data gaps were in tropical developing countries, that are rich in biodiversity but often lack the resources to study it,” said lead author Carsten Meyer of the University of Göttingen. “Our study adjusts and refines this impression and demonstrates the need to carefully assess and close these gaps.”

Additional co-authors of the study are Holger Kreft of the University of Göttingen and Rob Guralnick of the University of Florida-Gainesville.

For more information about the Map of Life, visit the website.

View article on Yale News

Sunday, September 6, 2015 // Jonas Pulver / Le Temps

Avec Map of Life, le big data et la géocalisation s’allient pour faire de vous un explorateur averti, voire un biologiste enrichissant la plateforme de ses observations

Vous êtes-vous jamais demandé quels étaient tel étrange oiseau croisé en voyage, telle fleur rencontrée en randonnée ou tel batracien baillant au bord de l’étang? Grâce au big data et à la géolocalisation, il suffit désormais d’un smartphone pour se muer en explorateur averti du grand jardin de la vie. L’initiative en revient à Map of Life, un effort de recherche international coordonné par l’Université de Yale.

Une fois l’app téléchargée, il suffit d’activer la fonction «What’s around me» pour connaître la composition de la flore et la faune alentour. Sur l’île de Miyajima au Japon (où cette chronique a été écrite), on trouve par exemple 229 oiseaux, 39 mammifères, 3 tortues, 19 amphibiens, 48 coléoptères et 19 conifères. A chaque espèce correspondent une fiche signalétique, des images et une carte des zones d’habitat.

Il y a plus: Map of Life est mise à jour en fonction des dernières observations par satellite, études académiques, bases de données et recensements. L’utilisateur lui-même peut identifier des espèces et/ou découvrir leur présence en sauvegardant et partageant ses observations sur la plateforme. «Les changements environnementaux, les disparitions d’espèces ou les invasions sont des irrégularités qui restent difficiles à détecter par satellite», explique dans un article le professeur Walter Jetz du Département d'écologie et l'évolution de Yale. «Vos marches en forêt, dans le désert ou dans les prés pourraient devenir des ressources inestimables pour la compréhension locale et globale de la biodiversité.»

Map of Life, pour iPhone et Android. Gratuit

View article on Le Temps

Tuesday, August 11, 2015 // Gregory R. Goldsmith / Science Magazine

The field guide, rebooted. Map of Life joins a small but growing number of mobile applications seeking to reimagine the field guide by combining big data and mobile technology. Reviewer Gregory R. Goldsmith takes the app for a test drive, breaking down its pros, cons, and its potential for attracting a new generation of ecologists.

View article on Science Magazine

Saturday, August 8, 2015 // Jessica Baldwin / Al Jazeera English

Walter Jetz has been working on the Map of Life app for four years. He's an expert in biodiversity, teaching at both Yale University in the US and Imperial College in the UK.

I caught up with him on a slightly overcast day on a picnic table in the leafy grounds of Silwood Park, Imperial College’s campus about 40km west of London, where he explained how the app works.

Touching the light blue icon with a three-branched tree opens the Map of Life, clicking on "What's Around Me", brings up a list including amphibians, butterflies, bees and 180 birds.

"We can move on to the songbirds, there are all sorts of tits and warblers around me that we can hear and then connect up with the app," Jetz told Al Jazeera.

More than 20,000 people from Brazil to Indonesia to South Africa have downloaded the app since it launched two months ago. Jetz said five to 10,000 people log on daily.

"The exciting thing about the app is it’s not just a field guide; it’s a flipped field guide. So instead of you having to sift through pages and pages of a field guide to identify that species you’ve just seen," Jetz said.

"It’s already a tailored list of species where you are right now."

The app is an international collaboration with scientists and computer programmers funded in part by NASA and the National Science Foundation in the US.

Valuable information

There are 35,000 species on the app across the globe but it’s not just meant to be fun in the park; science and biodiversity are the core.

Users in remote parts of the world, particularly near the Equator, are encouraged to report back their sightings.

Jetz said the citizen scientists are providing valuable information. He said app users in Java had spotted a turtle not seen for many years.

"You’d be surprised for one or two of those (turtle) species we barely have any information at all," Jetz said. "We have a rough map but no points on the ground that would tell us in detail where the species would be found."

The sightings are pinpointed by the phone's built-in GPS and added to the ever growing database.

Jetz said the app comes at a critical time as many species are changing fast - some becoming dominant in a region, others moving to different areas.

"Suddenly, we have information about potential threats, potential risks of extinction….which allows us to paint a detailed picture of where the species is and how its range may fair in the future," said Jetz, whose enthusiasm for wildlife was sparked by a childhood in Bavaria and is undimmed.

The data can be passed on to policy makers who can then decide if another agriculture project in a region is a good idea or if it will harm nearby species and impact biodiversity.

There are plans to add to the app’s six languages and within a few months there will be sounds the animals make to improve identification.

The pictures and text are easy to understand; I used the app in New York’s Central Park last month when I spotted a bright orangey-red bird with a matching beak, sure enough the Map of Life identified it as a Northern Cardinal.

View article on Al Jazeera English

Friday, July 10, 2015 // Yale Alumni Magazine

When the ornithologist and painter Roger Tory Peterson published the first modern field guide in 1934, he solved one of the biggest problems in species identification. No longer was it necessary to shoot or catch a creature and take it to an expert to find out its name; all you needed was the Field Guide to Birds (or one its many successors, which cover all sorts of living creatures)—along with sharp eyes, patience, and fast fingers to turn the pages.

Now, thanks to smartphones and “big data,” an effort is under way to create field guides that can tell you what’s around even before you lift the binoculars or the magnifying lens. A field guide of this sort was recently launched by Map of Life, an international research effort headquartered at Yale’s Program in Spatial Biodiversity Science and Conservation.

The Map of Life app shows what kinds of life surround you, no matter where you are in the world. When you request information on a particular group (mammals, birds, amphibians, trees, wildflowers, turtles, dragonflies, butterflies, or fish—a collection that is growing rapidly), the app delivers an inventory of all the species believed to be in your area. It also provides images, range maps, and authoritative natural history information, so you can satisfy your curiosity about the frog or butterfly you just glimpsed. The data are culled from scientific literature and public databases, along with satellite remote-sensing, so the app is constantly updated. The predictions of where and when species may occur are generated using the latest modeling techniques. The app also makes the study of natural history more interactive. Therein lies great scientific utility. The gaps and uncertainties in our data on spatial biodiversity can be huge, and they put constraints on scientific undertakings such as assessments of species status and trends, monitoring of species invasions, resource management, and ecological research. Changing environments and species losses and invasions are on the horizon, yet there is no satellite system or other system to monitor these perturbations and few means for biologists to assess and predict the consequences.

But detailed observations from individuals, especially in understudied regions, could advance our knowledge significantly. Armed with mobile technology, amateurs can become citizen scientists, sharing their observations and helping to fill in the gaps. Your hike into the woods, the desert, or the prairie could become an invaluable resource for our global and local understanding of biodiversity.

View article on Yale Alumni Magazine

Tuesday, June 30, 2015 // Teresa Shipley Feldhausen / Science News

Part interactive field guide, part map, a new app compiles millions of records on species ranges worldwide. By pinpointing your location, the Map of Life app lets you explore plants and critters you might see nearby. Or tap around the globe to see what might be blooming in Singapore, for example. Click on a species name to reveal its range map (one shown below), as well as crowdsourced pictures.

A team led by Walter Jetz of Yale University and Robert Guralnick of the Florida Museum of Natural History spent two years creating the Map of Life app, which is free for iPhones and Android. “The story of biodiversity is a visual one,” Guralnick says. Citizen scientists can help tell that story by reporting species sightings.

The Map of Life team plans to add a way to access records even without cellphone service. That could come in handy if you’re trying to figure out if that backcountry berry is edible.

View article on Science News

Tuesday, June 30, 2015 // Wired

Wednesday, May 20, 2015 // KARL GRUBER / ABC

A NEW MOBILE APPLICATION can tell you what wildlife species, animal or plant, may be living nearby.

The app estimates your location and provides information and photos about species that could be living near your location. The app relies in the vast Map of Life (MOL) database, an international effort "that aims to advance and share the global knowledge about the distribution of biodiversity in space and time and to provide a resource for mapping and monitoring species worldwide," says Dr Walter Jetz, a senior scientist in the Grand Challenges in Ecosystems and Environment group at Imperial College London.

The MOL app currently hosts information for more than 30,000 species from around the world, including birds, mammals, amphibians, butterflies, trees, and much more.

"The app puts a significant proportion of our global knowledge about biodiversity in the palm of your hand, and allows you to discover and connect with biodiversity in a place, wherever you are," says Jetz.

The novel application, currently available for Android and Apple iOS, also comes with a recording feature, which allows users to make their own notes of new sightings or any other relevant observation, which can then be added to the MOL database and shared with the wider community.

Jetz hopes this new application will help users change the way we identify and learn about the wildlife we see when travelling, walking in the bush or even stepping out into our own backyard, he says.

The app was released last week and already users worldwide are flocking to use it, notes Jetz. "…thousands of users worldwide are already using it to discover and connect with biodiversity and share their observations with friends or the project. Map of Life research is underway to use this and other information, including remote sensing, to better map and monitor species," says Jetz.

In the future, the MOL app plans expand its database to include more species and to allow for stand-alone use, for when the celluar network is out of reach, says Jetz. "On the research front and including scientists from all over the world, the project is contributing to multiple global biodiversity status and trend assessments," he adds.

View article on ABC

Wednesday, May 13, 2015 // Science Daily

The free Map of Life app dispenses with bulky field guides by allowing users to access a vast global database of species and their ranges, based on their location.

Building on the Map of Life website, which provides a database of everything from bumblebees to trees, the app tells users in an instant which sets of species are likely to be found in their vicinity. Photos and text help users identify and learn more about what they see. The app also helps users create personal lists of observations and contribute those observations to scientific research and conservation efforts.

"The app puts a significant proportion of our global knowledge about biodiversity in the palm of your hand, and allows you to discover and connect with biodiversity in a place, wherever you are," said guiding force behind the Map of Life Professor Walter Jetz, a Senior Scientist in the Grand Challenges in Ecosystems and Environment group at Imperial College London and an associate professor at Yale University.

"This vast information, personalized for where we are, can change the way we identify and learn about the things we see when traveling, hiking in the woods, or stepping in our own back yard."

Instead of sifting through hundreds of pages in a printed field guide, naturalists get a digital guide that is already tailored to their location. With a novel modelling and mapping platform covering tens of thousands of species -- everything from mammals and birds to plants, amphibians, reptiles, arthropod groups, and fish -- Map of Life presents localised species information via maps, photographs, and detailed information.

Thanks to a recording feature, citizen scientists everywhere can log their bird encounters and dragonfly sightings directly into the app and add to the biodiversity data available to scientists around the world.

"Think of a field guide that continues to improve the more we all use it and add to it. That is the beauty of this mobile application, and its great strength," said Rob Guralnick, associate curator at the University of Florida and the project's co-leader. "Built from 100 years of knowledge about where species are found, we hope to accelerate our ability to completely close the many gaps in our biodiversity knowledge."

Indeed, making it easier and more globally streamlined for citizen scientists to contribute information is one of the key motivations behind creating the app. "The world is changing rapidly and species continue to disappear before we even knew where they occurred, what role they had, and how we could conserve them," said Professor Jetz, who is involved in several global science initiatives for advancing biodiversity monitoring.

"Too much of our knowledge is limited to too few places and species," said Professor Jetz. "Helping people everywhere to identify and then record biodiversity carries the potential to hugely extend the geographic and taxonomic reach of measuring the pulse of life."

The Map of Life app is available in six languages for iPhone and Android smartphones, and can be downloaded from https://mol.org/mobile.

The National Science Foundation and NASA provided initial support for Map of Life and Google and Senckenberg Gesellschaft für Naturforschung also have supported the project.

View article on Science Daily

Wednesday, May 13, 2015 // Jim Shelton / Yale News

Never has knowledge of the world’s biodiversity knowledge been more at your fingertips, thanks to a new smartphone app: the Map of Life. No matter where you are, the app can tell you what species of plants and animals are nearby.

Building on the Map of Life’s unrivaled, integrated global database of everything from bumblebees to trees, the app tells users in an instant which species are likely to be found in their vicinity. Photos and text help users identify and learn more about what they see. The app also helps users create personal lists of observations and contribute those to scientific research and conservation efforts.

“The app puts a significant proportion of our global knowledge about biodiversity in the palm of your hand, and allows you to discover and connect with biodiversity in a place, wherever you are,” said Walter Jetz, a Yale University associate professor of ecology and evolutionary biology, and the guiding force behind Map of Life. “This vast information, personalized for where we are, can change the way we identify and learn about the things we see when traveling, hiking in the woods, or stepping in our own back yard.”

Instead of sifting through hundreds of pages in a printed field guide, naturalists get a digital guide that is already tailored to their location. With a novel modeling and mapping platform covering tens of thousands of species — everything from mammals and birds to plants, amphibians, reptiles, arthropod groups, and fish — Map of Life presents localized species information via maps, photographs, and detailed information. The National Science Foundation and NASA provided initial support for the Map of Life. Google and Senckenberg Gesellschaft für Naturforschung also have supported the project.

Thanks to a recording feature, citizen scientists everywhere can log their bird encounters and dragonfly sightings directly into the app and add to the biodiversity data available to scientists around the world. “Think of a field guide that continues to improve the more we all use it and add to it. That is the beauty of this mobile application, and its great strength,” said Rob Guralnick, associate curator at the University of Florida and the project’s co-leader. “We hope that the Map of Life app, built from 100 years of knowledge about where species are found, will accelerate our ability to completely close the many gaps in our biodiversity knowledge.”